The last two logs were retrieved from Dyvig and split. Here we discovered two new unfortunate conditions. Firstly, the logs had been attacked by pileworms, a phenomenon that had recently been found in Dyvig Boat Club's mooring poles, and secondly, both of the remaining two logs had loose heartwood. Fortunately, the pileworm infestation was largely limited to the sapwood (the outermost 3 cm of the trunk under the bark), which was not to be used anyway.

However, the loose heartwood made it necessary to glue the two railing planks together to achieve a sufficiently large width.

As mentioned, the railing had to have a curvature to prevent the boat from sheering too much. A curvature with an arrow height of 12 cm was chosen.

The plank had to be cut flat with a thickness of 1.5 cm.

The top cleat had a hint of having been curved with the convex part facing upwards. After some discussion, it was decided that its function would be to prevent the end of the thwart, from moving in a forwards or backwards direction.

As mentioned, the wood for the railing planks was not wide enough. The railing planks were installed provisionally to show how much wood was missing.

A series of planks were produced to be glued to the formed glue surfaces of the railing planks. The procedure was the same as for the bottom plank. The work of forming the gluing surfaces was a very large and time-consuming task. It is estimated that the additional gluing work took a total of 1,000 working hours for the bottom plank and the two railing planks combined.

After the gluing process and the removal of the screws, the railing planks were cut to size. The weight of a finished railing plank was 74kg.

The planks were assembled in the same way as the side planks, starting at the centre of the ship with both planks and then continuously adjusting, sealing and stitching towards the bows.

When the railing planks were fully assembled, the boat shell was finished and showed the elegant lines of the Hjortspring boat. The hull, as it stood, weighed around 400kg.

The taut rope hypothesis

On the upper side of both bows, just outside the boat room, there were four parallel cleats orientated in the longitudinal direction of the boat. Their function caused much discussion. Unlike the other cleats, which each had a square hole with an 8 mm edge length, the bow cleats had a rectangular hole measuring 10 by 26 mm. This suggested that they were to be used for two ropes, one going outwards towards the horns and one going inwards towards the boat room.

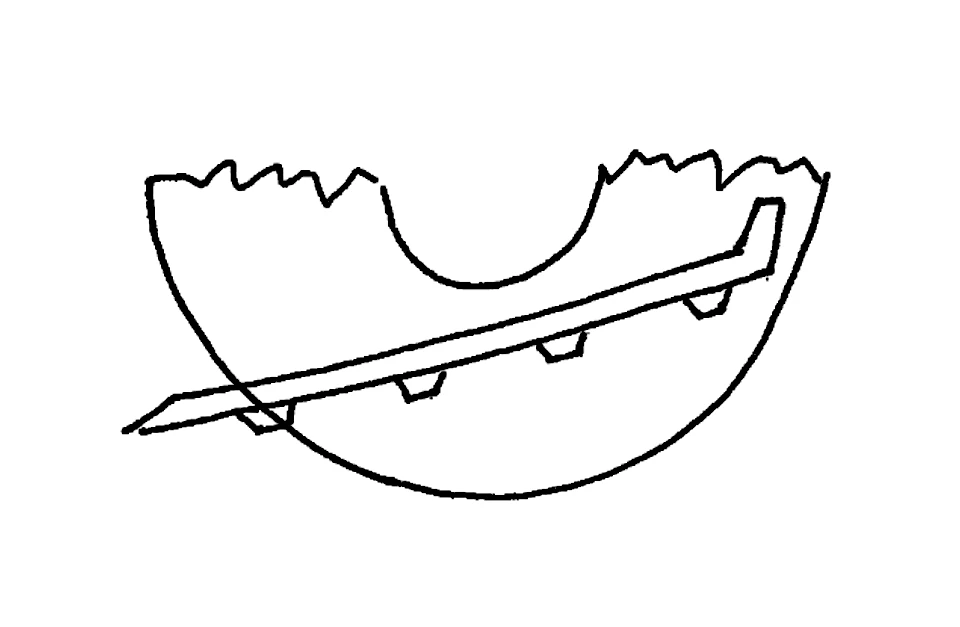

It was hypothesised that these cleats would be used to secure the mooring ropes and also formed a four-cut block to secure and tighten a longitudinal taut rope that would run between the two bows. This taut rope was to prevent the boat from keel cracking.

Keel cracking can be explained as an upward bending of the centre of the boat during sailing, and the phenomenon is known in all wooden ships. For example, the Fregatten Jylland was more than a metre keel-bent when it was chocked up on its final berth in Ebeltoft. A ship as tapered at both ends as the Hjortspring boat will have its significant buoyancy from the middle 6 metres, while its load is evenly distributed over 12 metres. The front and rear paddlers are almost floating in the air without buoyancy from the boat directly below them.

A tension rope would counteract the tendency for keel cracking. Egyptian petroglyphs from 1,200 BC show such ropes.

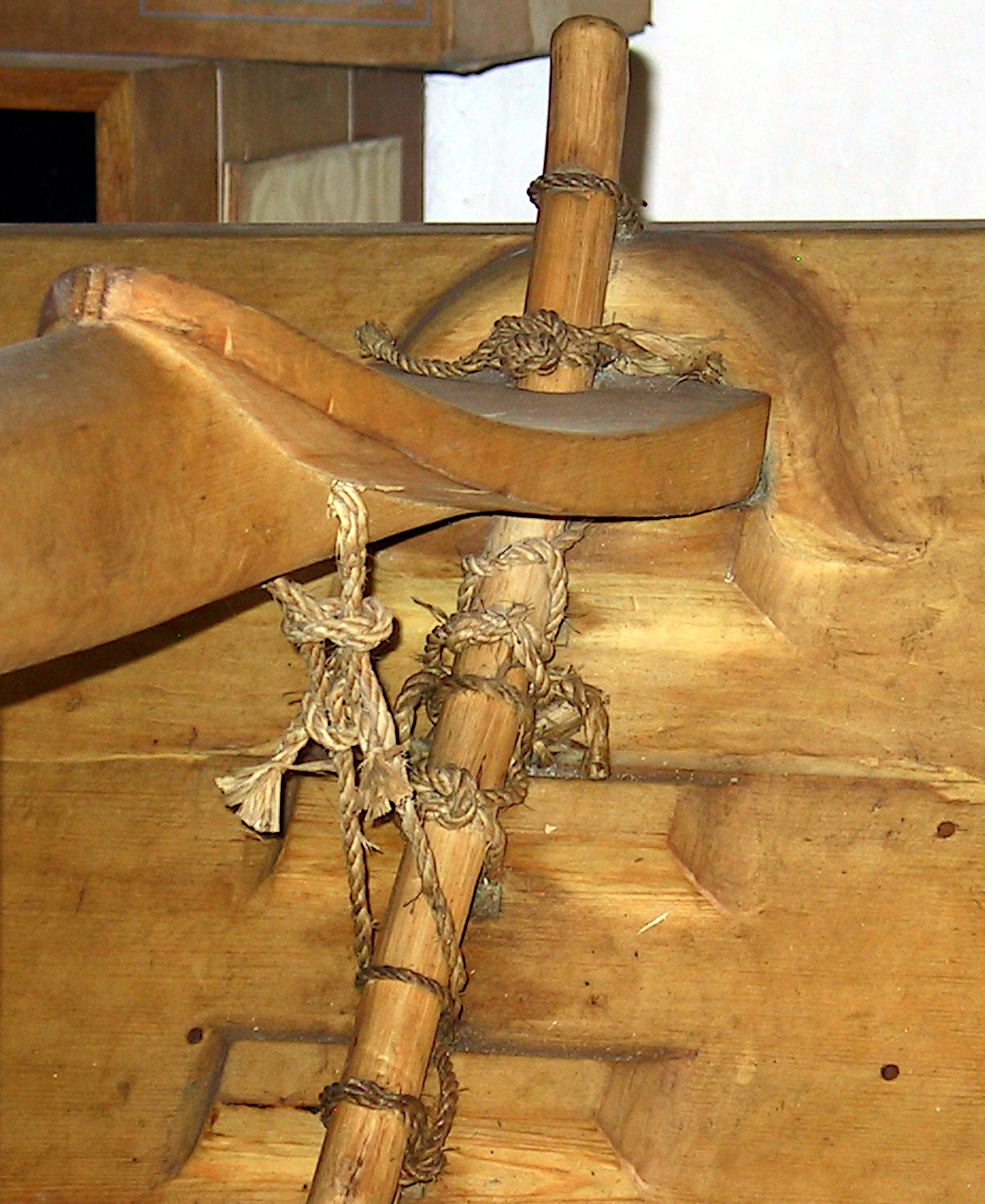

An 8 mm hemp rope (linden bast was too expensive for us) was tensioned and ran back and forth between the two sets of cleats, forming a four-cut waist. This was tightened up and prevented the bows from sinking downwards even during construction. In order to tighten the rope easily, a cross-pin was attached that could twist the seven longitudinal cords together and adjust the rope's tension as needed, even during sailing.

We realised that this use of the two times four cleats as blocks for a tension rope was a hypothesis, and only sailing would eventually determine how likely it was.