How we got started

We started by defining what we wanted and how:

Prioritering

In any project that contains unknown elements, it is necessary to prioritise a number of parameters or aspects in relation to each other. Not all can be equally important. This is an approach used in the development process at Danfoss. The typical method is to identify 5 parameters, prioritise them by importance and leave the last one as the free parameter to deviate from the plan when difficulties arise.

The prioritisation should be understood in the sense that whenever two parameters were competing, the parameter with the highest importance should prevail. In this case, the following parameters were chosen to reflect the objective: to illustrate the functional value of the boat as a gateway to a better understanding of the society of the time, while contributing to the growing understanding of the evolution of boat construction in ancient times.

However, it was not the case that we chose these parameters before we started. They emerged through an organic development over the first few years.

The prioritisation should be understood in the sense that whenever two parameters were competing, the parameter with the highest importance should prevail. In this case, the following parameters were chosen to reflect the objective: to illustrate the functional value of the boat as a gateway to a better understanding of the society of the time, while contributing to the growing understanding of the evolution of boat construction in ancient times.

However, it was not the case that we chose these parameters before we started. They emerged through an organic development over the first few years.

- Quality in all aspects of the project.

- Seriousness in choosing solutions.

- Representation of the latest interpretations.

- Documentation of all actions and choices.

- Time spent building the boat.

The five parameters are prioritised and their content is illustrated below. First, however, let's show an example of the effect of prioritisation. At an early stage, we had to choose which material the boat's planks were sewn together with. True to the Seriousness parameter, we studied the literature to see what materials were typically used for cords in the Iron Age. It seemed that cords made from linden bast were widely used throughout antiquity. Conservator G. Rosenberg, who had excavated the boat in 1922 and described and interpreted the find in 1937, had suggested linden bast cords, not least because a bundle of cords made from this material had been found as part of the find. Some cords were made and a tensile test showed sufficient strength.

However, the latest interpretations by the National Museum of Denmark's Marine Archaeological Survey (NMU) suggested that the use of birch roots could be a solution. However, the arguments in favour of this last solution did not seem convincing to us, which is why we ultimately retained lime bast cords as the chosen solution. An example of a different prioritisation than the one chosen here can be seen in the book ‘Roar Linde’, where a scout troop in 1971 built a replica of the Hjortspring boat together with people from Vikingeskibshallen in Roskilde. Here the prioritisation must have been (if we use the same five parameters):

However, the latest interpretations by the National Museum of Denmark's Marine Archaeological Survey (NMU) suggested that the use of birch roots could be a solution. However, the arguments in favour of this last solution did not seem convincing to us, which is why we ultimately retained lime bast cords as the chosen solution. An example of a different prioritisation than the one chosen here can be seen in the book ‘Roar Linde’, where a scout troop in 1971 built a replica of the Hjortspring boat together with people from Vikingeskibshallen in Roskilde. Here the prioritisation must have been (if we use the same five parameters):

- Schedule (and money).

- Tools.

- Documentation.

- Quality.

- Seriousness.

The result was a boat that was half a metre narrower than the one the find indicates, with ‘’lamentable‘’ horns and a very rough finish, presumably made for 1/10 of the price of the Tilia. Results from the test have not been published.

Differences in prioritisation result in crucial deviations in solutions.

Differences in prioritisation result in crucial deviations in solutions.

Product quality

This parameter became the most important throughout the course of the project, in the boat building as well as in the work of the other groups.

A healthy acceptance of comments from colleagues regarding the quality of one's own work developed and resulted in a high level of refinement of the boat and its details. The monthly meetings had the same effect, where the assembly commented on the individual groups' reports with “cordial candour”.

A healthy acceptance of comments from colleagues regarding the quality of one's own work developed and resulted in a high level of refinement of the boat and its details. The monthly meetings had the same effect, where the assembly commented on the individual groups' reports with “cordial candour”.

Seriousness

A lot of work went into obtaining previous descriptions of the boat and finds. These were analysed and discussed in depth. A 1:10 scale model of the boat was made. Every detail of the boat was discussed. Parts were made for the sole purpose of being the subject of discussion.

The reasons for choosing solutions often came from other parts of the boat or from other boats.

A few choices were so revolutionary that they were labelled hypotheses, or preliminary theories, and the value of the choice would later be examined during testing of the finished boat.

Based on the literature, tools were made, tested and modified.

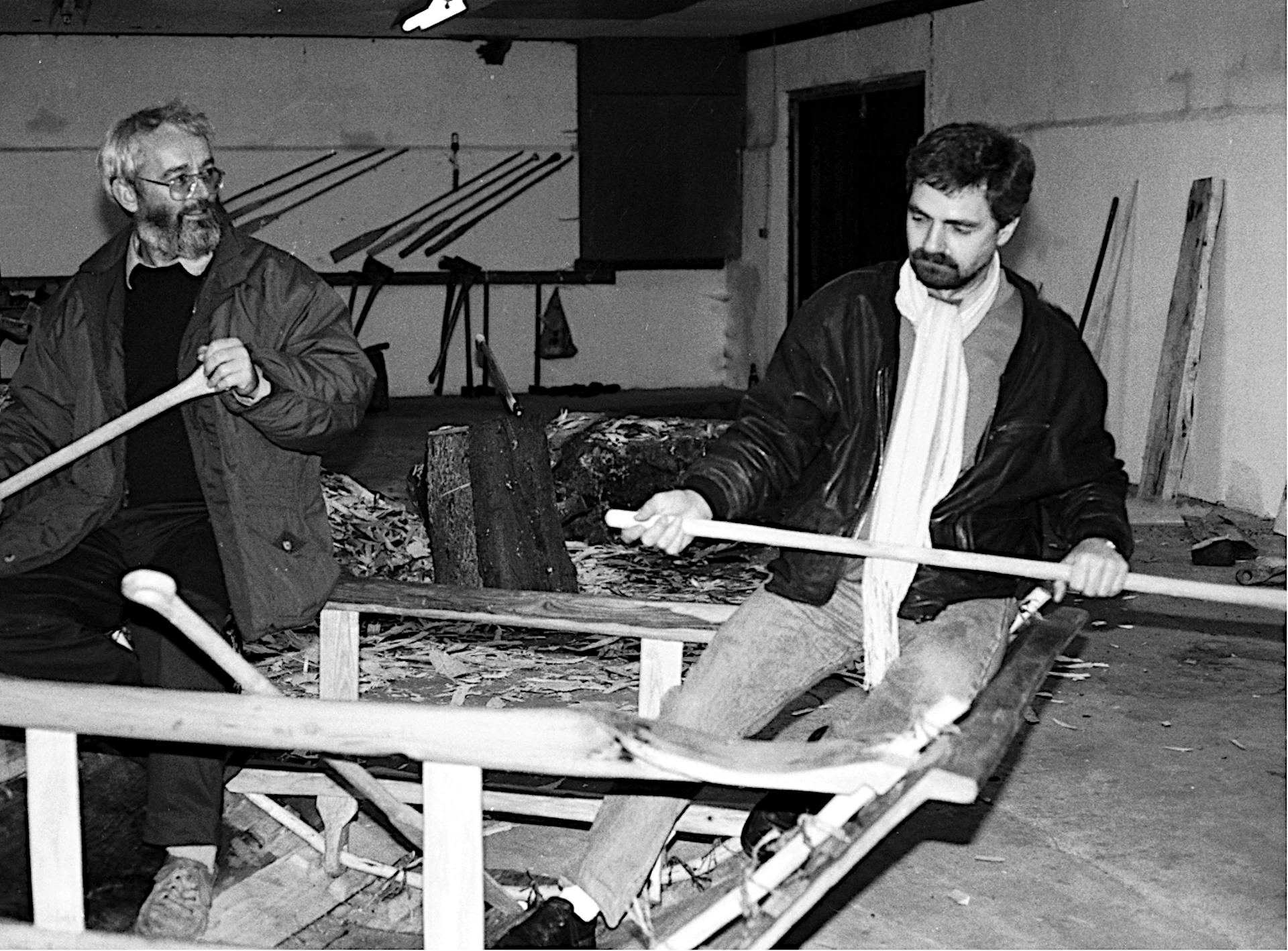

An intensive woodworking practice period was carried out with the manufactured tools..

The reasons for choosing solutions often came from other parts of the boat or from other boats.

A few choices were so revolutionary that they were labelled hypotheses, or preliminary theories, and the value of the choice would later be examined during testing of the finished boat.

Based on the literature, tools were made, tested and modified.

An intensive woodworking practice period was carried out with the manufactured tools..

Representation

To ensure that the replica would represent the latest interpretation, the guild liaised with various scientists at museums and universities. The guild formed what we called our ‘Scientific Network’. Throughout the project, these scientists were contacted regularly by phone and by visiting the museums.

For the first few years, people from the National Museum's maritime department in Roskilde inspected the boat building twice a year to comment on the solutions. The members of the scientific network received the membership folder and regular reports.

For the first few years, people from the National Museum's maritime department in Roskilde inspected the boat building twice a year to comment on the solutions. The members of the scientific network received the membership folder and regular reports.

In accordance with our prioritisation parameter ‘Seriousness’, the scientists' statements were “taken with a grain of salt”. We were supposed to contribute to increased knowledge about the boat through our work and should therefore represent the latest truth in our interpretation.

In other words, the idea was that our work should stand on the shoulders of established knowledge.

In other words, the idea was that our work should stand on the shoulders of established knowledge.

Documentation

From the start, it was considered essential to record all activities and results in print or on photo/video. This attitude is very important in that a finished boat without documentation is just a boat and not a piece of scientific work from which new insights could be drawn.

Without documentation, much of the work and money invested would be wasted.

The various media that were used as documentation are described above. Most recently, the guild has published a website describing its history and activities (the one you are reading right now).

This book is also an example of documentation.

The focus on documentation had a crucial impact on the quality of the work.

Nobody wants to write a report describing careless choices.

Without documentation, much of the work and money invested would be wasted.

The various media that were used as documentation are described above. Most recently, the guild has published a website describing its history and activities (the one you are reading right now).

This book is also an example of documentation.

The focus on documentation had a crucial impact on the quality of the work.

Nobody wants to write a report describing careless choices.

Tidsforbrug

The time spent building the boat was continuously recorded, so that when people arrived to work on the boat, they signed in the logbook, just as they signed out when they left the shipyard to go home.

Coffee breaks were included as part of the work, as they were very much used to discuss solutions to problems.

As mentioned, time consumption was counted as the free parameter. The time needed to achieve the best possible result was available.

Coffee breaks were included as part of the work, as they were very much used to discuss solutions to problems.

As mentioned, time consumption was counted as the free parameter. The time needed to achieve the best possible result was available.

Sources

Language

The text in this article has been translated from Danish to English using the free DeepL translation programme.